The Etymology, Origins, and History of Andon

Andon Lanterns in Edo Japan

The Etymology of Andon

The English word Andon is derived from the Japanese word 行灯, which loosely translates to "paper-enclosed lantern." The defining characteristics of Andon lanterns are their frames (often made with wood) and their windbreak covers (often made with washi paper). Washi paper is a traditional handmade Japanese paper that is very durable due to its long fiber construction. Traditional Andon lanterns also often include a shelf to hold a bowl for oil and wick.

History of Andon: Edo Period of Japan

The Andon style of lantern was especially popular during the Edo period of Japan (1603 to 1867), which was the final period of traditional Japanese culture - a time of relative peace and prosperity, a time of shogunate and samurai.

During the Edo period, the social order was limited to four classes: samurai, farmer, artisan, and merchant. The Andon was used for indoor lighting across the classes and by merchants to identify their shops. Ironically, merchants were at the bottom of the social order. They were seen as adding little value because they didn’t make anything. Score one for manufacturing - we make things!

The Edo period was named after the tiny fishing village of Edo, which at the time consisted of several hundred cottages and a castle in considerable disrepair. However, after the Tokugawa shogunate chose Edo for its center of power, the castle was rebuilt, and the city exploded in size, soon becoming the most populous city in the world.

Endings and Beginnings - The Return of Imperial Rule

Ironically, it was the arrival of Americans in Edo Bay in 1853 via a fleet of Navy ships led by Commodore Perry that hastened the fall of the Tokugawa regime and the restoration of imperial rule in Japan. It became painfully clear that Japan had not kept pace technologically or militarily, and in 1867, power was wrested from the shogunate by two powerful imperialist clans: the Choshu and Satsuma.

The following year, imperial rule was restored in the name of the 14-year old Emperor Meiji. The imperial residence was moved from Kyoto to Edo, which was renamed to Tokyo (loosely translated as “East Capital” or “Kyoto of the East”). Thus began the Meiji era of Japanese history.

Bright Lights - Gas, Kerosene, and Electricity

The Meiji period saw a decline in the use of Andon lanterns in Japan. The first gas light was installed in 1872, and electricity was introduced in 1878. Around the same time, kerosene lamps became popular as they were brighter, easier to use, and safer than Andon lanterns. Japan developed a cultural affinity for bright lights, which were seen as symbols of prosperity.

Masao Inui, Tokyo Institute of Technology

Japan had an interesting role to play in lighting, even as the use of Andon lanterns declined. While inventing the light bulb, Thomas Edison tested an astounding number of materials to find a workable filament. Out of the thousands of materials he tested, the most effective material, and the material that he commercialized, was carbonized bamboo initially sourced from the bamboo forests of Kyoto.

Andon Visual Controls in Manufacturing

Who Invented the Andon?

Taiichi Ohno, the driving force behind the Toyota Production System, can reasonably be considered the inventor of the Andon in manufacturing. But the history of the Andon is much more interesting than one name - so let's trace Andon origins back to 1896 and the invention of an improved power loom.

Sakichi Toyoda and the Power Loom

Power looms are mechanized devices for weaving textiles. Although power looms were known as far back as 1786, Sakichi Toyoda made a series of important improvements to the power loom. In fact, he held 38 patents related to looms (source: Toyota Motor Corporation; Overview of Sakichi Toyoda's Inventions).

One of these patents was for a feature to automatically shut down the loom if the weft thread (which is woven through the stationary warp thread in a loom), broke or ran out. This enabled looms to run unattended for the first time. In other words, one person could operate multiple looms.

Sakichi Toyoda's eldest son, Kiichiro Toyoda, worked under the direction of his father to further improve the power loom. In 1926, the Toyoda Automatic Loom Works was established, with Kiichiro as Managing Director, to manufacture the Type G Automatic Loom.

Taiichi Ohno started his career at Toyoda Automatic Loom Works. As such, he was an expert in the power loom, and he later acknowledged that the design of the power loom was the inspiration for one of the two pillars of the Toyota Production System - Jidoka.

Jidoka roughly translates to “automation with a human touch.” The core idea is to design equipment to automatically stop when a problem is detected. Sound familiar?

As a side note, the Toyoda Automatic Loom Works also launched an Automotive Production Division in 1933, which was spun off into Toyota Motor in 1937.

Andons as a Form of Jidoka

Andons developed at Toyota as a type of Jidoka. The Toyota Production System Guide (Toyota PLC) defines two forms of Jidoka:

- Design equipment to automatically stop when a problem occurs (mechanical Jidoka)

- Equip operators with the means to stop production when they observe a problem (human Jidoka)

The Andon is essentially human Jidoka. Plant floor operators, as experts in their domain, are permitted (perhaps even obligated) to pull the cord to stop production if they perceive a potential quality issue or some other irregularity.

Andon Origins at Toyota

One of the earliest authoritative descriptions that uses the term Andon in relation to manufacturing can be found in the book Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production, written by Taiichi Ohno.

The Ford Perspective on Andons

The history of Andon would not be complete without mentioning Ford Motor Company. In his 1931 book Ford Men and Methods, Edwin P. Norwood describes a system used at the Ford Rouge plant that has much in common with Andons:

It is interesting to see that at Ford, like Toyota, pulling the cord was seen as an operator responsibility (perhaps even an obligation).

There is no question that the Andon as we know it today had its origins in the Toyota Production System. However, as described next, there is also no question that Ford had a huge influence on Toyota.

Connections and Influences

The connections between practices at Ford and those at Toyota are not at all surprising. Taiichi Ohno spent considerable time studying the Ford mass production system and was a great admirer of Henry Ford. He wrote:

It is very refreshing to see the shared passion that existed at Ford and Toyota for driving improvement and doing so in a way that empowered their employees.

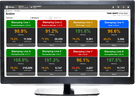

Today, more sophisticated visual indicators are often used as Andons, but their purpose – simple, efficient, real-time communication of manufacturing process status, and solving underlying problems with long-term fixes – remains the same.

While the principles of Andon are timeless, Vorne's XL Productivity Appliance brings them into the modern era with advanced visual controls, real-time monitoring, and actionable insights.